It’s probably a garden spider, only one Joro has been spotted in Massachusetts

There’s been a lot said about the introduction of the Joro spider into the United States, with the first spotted in Georgia in 2014.

Editor’s Note: Because many people do not like spiders and may be afraid of them, we broke this article into three parts. Part 1 is just the basic facts you need to know while Part 2 is for people who want to learn more. Then read Part 3 if you love spiders.

There’s been a lot said about the introduction of the Joro spider into the United States, with the first spotted in Georgia in 2014.

Part 1: Here’s some basic facts you need to know about the Joro spider:

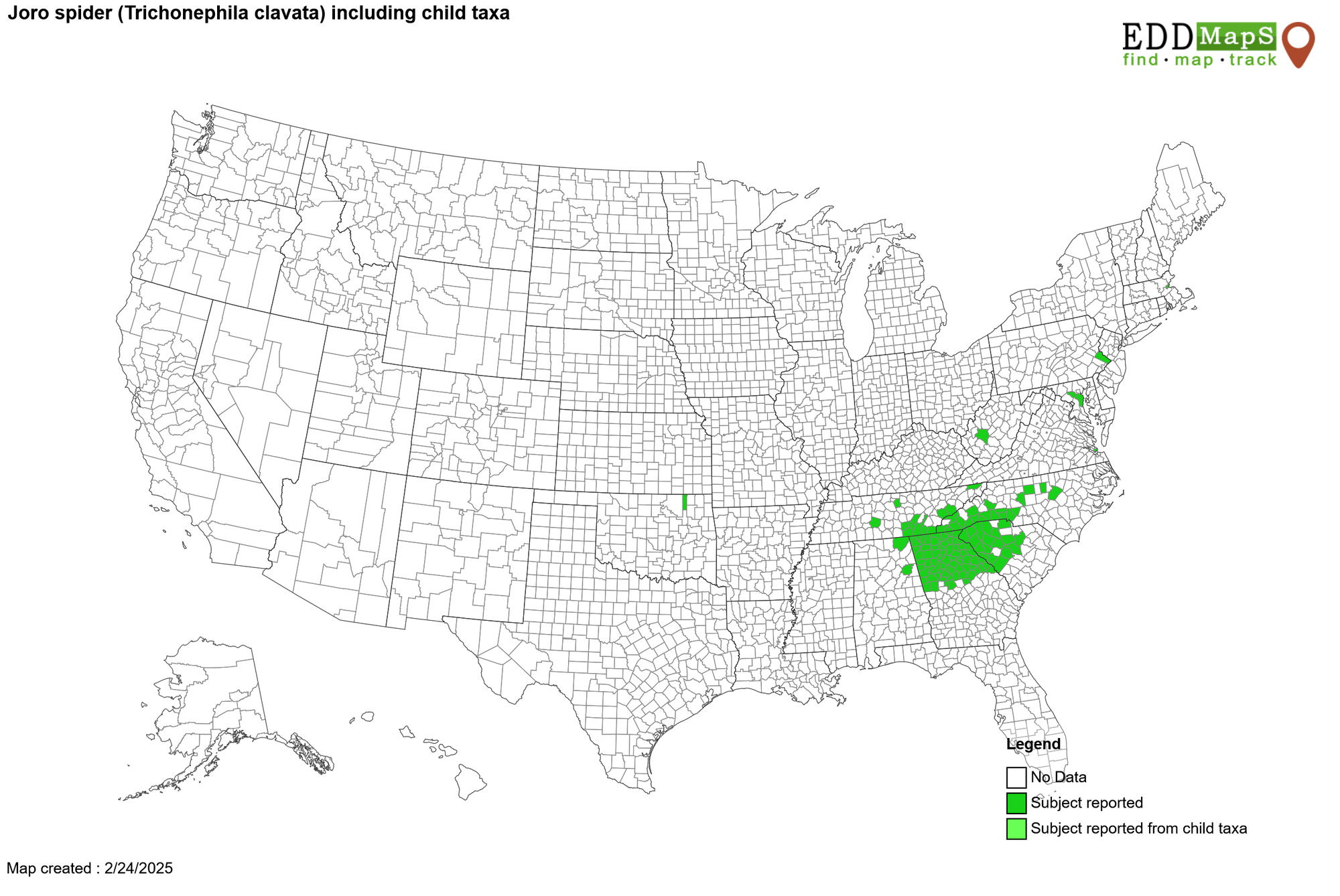

• The Joro spider is native to Asia and was introduced a little over 10 years ago in Georgia, where it has been reported in almost every county.

• Only one Joro has been reported in Massachusetts, and that was in Suffolk County in September 2024.

A map of the distribution of the species can be found at JoroWatch.org, which is maintained by the University of Georgia Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health, in partnership with several other organizations.

• The body of an adult female Joro spider can be up to 1.25 inches long, and she cannot fly.

• The spiderlings, which are tiny, use the wind to disperse.

As of the writing of this article, there is no indication that the Joro is dangerous to people, pets, or ecosystems. However, as invasive species go, the Joro is a recent introduction, so research is ongoing.

Part 2

You may have seen headlines like, “giant flying spiders may be arriving in your town,” which may conjure video of a tarantula flying over the picnic table during your family cookout and plunking down on your burger. That is not going to happen, because adult Joro spiders cannot fly.

So, what is the reality of the Joro spider in Massachusetts and what do they do?

Rebekah Wallace, who is the invasive species data coordinator at the University of Georgia Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health, and Jessica Garb, who is an associate professor at UMASS Lowell and has been studying spiders for about 30 years, talked about the Joros.

The spiderlings of many species of spider use a technique called “ballooning” to disperse. The Joro’s spiderlings balloon shortly after they hatch.

“The spiderlings will send out a thread,” Wallace says. “The thread will catch on the wind and they’ll move a little bit away from each other.”

They won’t go any great distance by ballooning.

The adult Joro that was spotted in Suffolk County was originally reported via iNaturalist and then incorporated into the data on JoroWatch.org, where people can report sightings of Joro spiders via a software program called EDDmapS.

“Anything that shows up on the map has been reviewed,” says Wallace, whose job includes helping people learn about the app, the website, and how to report.

“It’s possible that the adult crawled on a vehicle and got transported up there,” Wallace adds.

Much less likely, but also possible, is that an egg mass was transported, she says.

These spiders lay their egg masses on flat surfaces, such as a leaf, tree bark, the side of a building. An egg mass can be transported, but if that happened, there would probably be more sightings, she says.

“The average person can learn how to ID them because once you know the key features,” Wallace says. “There’s not a lot that will look like an adult female.”

The males of this species are considerably smaller and lack the bright colors of the female.

Garb says people should be aware there is at least one species in Massachusetts that could be mistaken for a Joro.

“I am concerned about people getting confused about the Joro and the garden spider,” says Garb, who studies spider silk and also teaches classes.

She’s talking about the black and yellow argiope, commonly known as the garden spider, which is a bit smaller than the Joro.

The female’s body tops out at about 1 inch long, but, Garb says, she has been contacted several times by people who have taken a photo of a garden spider and believe it’s the Joro.

The best thing to do, she says, is report sightings via JoroWatch, where the photos and data will go through the review process. Also, look at photos of the Joro and the garden spider side-by-side, she says, to see the differences.

“I think it’s important to be alert because it’s possible that it will be establishing itself here,” Garb says of the Joro. “We don’t really know for sure. Will they become super numerous? Nobody knows.”

As of the publication of this article on Feb. 24, 2025, there have been no new sightings in Massachusetts via JoroWatch.

Like almost all spiders, the Joro has venom.

“Spiders eat live prey and they need venom to subdue it,” Wallace says. “The question becomes is it medically significant for humans, pets, whatever. As far as we know, it is not.”

Garb says, “I just don’t think their behavior is consistent with them being likely to bite anything.”

Part 3

The Joro spider is an orb weaver, meaning the female makes a round web with many spokes, the kind of web most people associate with spiders.

Different parts of orb webs, Garb says, are composed of different silks.

“Many spiders, in fact, can make multiple different kinds of silk, and they have different properties,” she says.

The spokes of an orb weaver’s web are made of a stiff silk while the spirals are more stretchy.

“The spiral is stretchy because it has to bend with the energy of flying insects,” Garb explains, and the spiral has an additional layer of silk that is glue-based and sticky.

“They all kind of work together to catch things,” she says.

The Joro web is distinctive in that the spirals are close to each other, and that gives the web a net or lace-like quality, she says.

There are some 50,000 known species of spider, but not all of them make webs. Some species of jumping spider that are common in the Boston area, for example, are active hunters and use their silk for shelter. They do not use the silk for catching prey.

Among those spiders that do use webs, there is great diversity.

“They’ve evolved different behaviors that rely on these complex webs to catch different kinds of prey,” Garb says, and that allows them to occupy specific ecological niches.

Some spiders create lassos or slingshots out of silk to catch their prey.

“There’s a spider that has a modified orb web, very modified, and it basically sticks to water so it can catch insects that can be found in water bodies,” Garb says.

One of Garb’s favorite spiders (there are too many to pick just one) is the triangle web spider, which creates a web that looks like a sector of an orb web.

“I call it like a pizza slice of the orb web,” Garb says. “It basically holds onto it and releases it when the prey gets in there and then it collapses the web around the prey.”

The triangle web spider can also be found in the area north of Boston.