The Iceman Cometh: Boston’s hockey scene owes a lot to Italian-American know-how

If you’re reading these words over your morning coffee somewhere around Greater Boston, there’s a good chance you delivered your son or daughter to hockey practice a few short hours ago.

If you’re reading these words over your morning coffee somewhere around Greater Boston, there’s a good chance you delivered your son or daughter to hockey practice a few short hours ago.

But I wonder how many hockey parents realize that these pre-dawn training sessions owe a lot to an Italian-American inventor by the name of Frank Zamboni.

If you came of age around Boston in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as I did, it was impossible to overlook Zamboni’s most famous invention.

The Bruins were the town’s premiere team back then. The squad was made up of an endearing blend of journeymen and future hall of famers, and in many local households the TV was stuck on WSBK Channel 38, which carried a number of B’s games and featured a twice-weekly highlights show as well.

The club’s success also ignited a widespread interest in schoolboy hockey that continues to this day.

All those years ago, I thought “Zamboni” was just a generic manufacturer's name, like the Xerox machine. Little did I suspect the improbable tale of luck and initiative behind it.

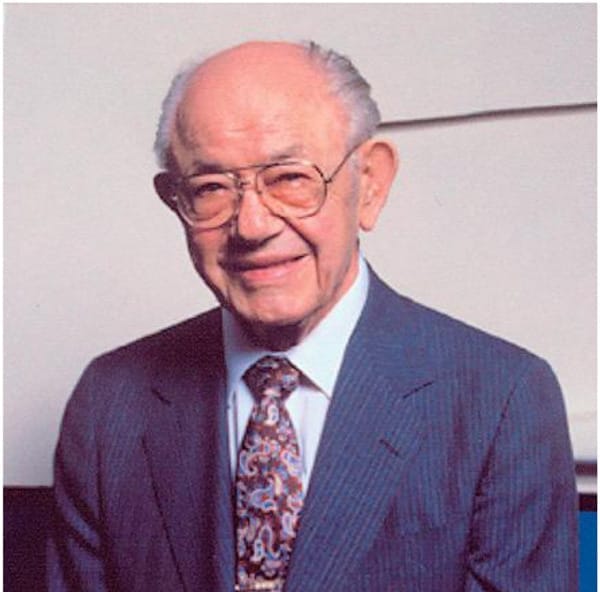

Born to immigrant parents in 1901 — fittingly enough in Eureka, Utah — Frank Zamboni moved with his family at the age of 2 to a farm in Idaho. Over the next two decades country life stirred an innate cleverness and can-do attitude in the young inventor.

Unlikely as it seems, though, the man whose name is now synonymous with ice-cleaning equipment developed his refrigeration skills in the dry and dusty surroundings of Southern California.

Heeding a call increasingly out of fashion these days, Zamboni felt that California was the place to be, and he moved there in 1920 to join his two brothers in a car repair business.

A few years later, the brothers branched out into the refrigeration business, building and installing the large chiller units used by local dairies to keep milk cool.

Diversifying once again, the Zambonis then built a plant to supply the block ice that California’s fruit and vegetable dealers needed to transport their produce by rail across the U.S.

But as industrial and domestic refrigeration techniques became more sophisticated and block ice an anachronism, the Zambonis’ business reached crisis point. The brothers caught a break with the improbable arrival of ice-skating in Southern California. The pastime was becoming increasingly popular, but there weren’t enough rinks to cater to demand.

Filling a gap in the market, Frank Zamboni, together with his brother and cousin, built Iceland, a rink that still operates today, overseen in part by the LA Kings hockey team.

At its opening in 1940, Iceland — located in Paramount, Calif. — boasted a floor area of 20,000 square feet, big enough to accommodate 800 skaters at one time.

Incredibly, the rink was at first an open-air attraction. As you might imagine, keeping the ice in fit shape for skating was a tricky job under the Southern California sun.

A roof was soon installed, which helped preserve the ice sheet for longer. Zamboni then confronted his next design test, namely, devising a technique to re-surface the ice quickly and efficiently.

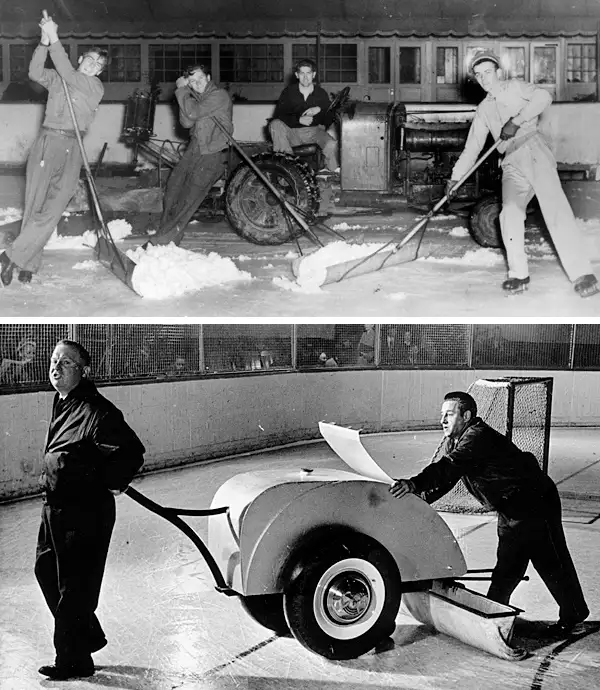

The old method of scooping up the shavings manually, spraying water over the ice, then smoothing it clean and waiting for the water to freeze, took more than an hour and was very labor intensive in a rink as big as Iceland. There had to be a better way.

In 1950, nearly a decade after Zamboni recognized the need to improve ice re-surfacing, Frank J. Zamboni & Co. was established across the street from the Iceland rink and the first Zamboni machines began appearing.

The story goes that Olympic figure skating champion Sonja Henie saw the machine in action and ordered one. Frank Zamboni then obliged his illustrious customer by driving it himself to Chicago.

But the man didn’t stop there. Zamboni’s later inventions included machines for removing excess water — or paint stripes — from artificial grass surfaces such as Astroturf. After his death in 1988, Zamboni received a fitting tribute: induction into the World Figure Skating Hall of Fame and the U.S. National Inventors Hall of Fame.

So the next time you’re shivering at rinkside, take a moment to admire the fine sheet of ice over which your son or daughter is gliding gracefully. And then raise a cup of hot coffee to the memory of Mr. Frank Zamboni.

Medford native Steve Coronella has lived in Ireland since 1992. He is the author of “Designing Dev,” a comic novel about an Irish-American lad from Boston who's recruited to run for the Irish presidency. His latest publication is the column collection “Entering Medford — And Other Destinations.”